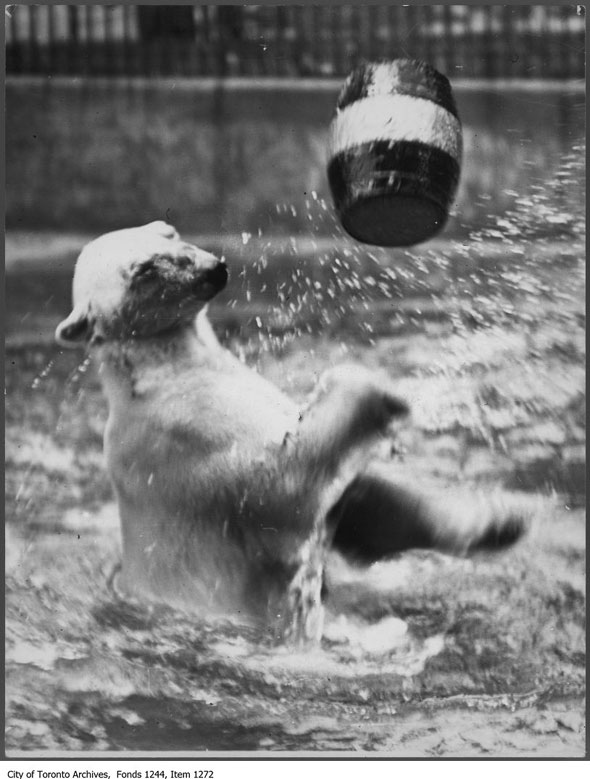

Toronto Zoo might get the pandas nowadays, but the land now occupied by Riverdale Farm used to be the city's premier animal watching institution. For 75 years Riverdale Zoo was home to a bizarre menagerie of wild and exotic creatures, including elephants, hippopotamuses, monkeys, and sea lions.

Toronto Zoo might get the pandas nowadays, but the land now occupied by Riverdale Farm used to be the city's premier animal watching institution. For 75 years Riverdale Zoo was home to a bizarre menagerie of wild and exotic creatures, including elephants, hippopotamuses, monkeys, and sea lions.

The historic Cabbagetown attraction closed for good and was partially demolished when the Metropolitan Toronto Zoo opened in 1975. Today, all that's left of the once thriving Victorian wildlife park with its decidedly dubious animal care policies is a scattering of historic buildings and a landscaped green space.

The land east of Winchester and Sumach streets that's now Riverdale Farm was once part of the estate of Henry Scadding, an early landowner on the Don River. In 1856, Toronto purchased a section his property for a new park and an industrial farm to be maintained by inmates at the Don Jail on the other side of the river.

The land east of Winchester and Sumach streets that's now Riverdale Farm was once part of the estate of Henry Scadding, an early landowner on the Don River. In 1856, Toronto purchased a section his property for a new park and an industrial farm to be maintained by inmates at the Don Jail on the other side of the river.

The 162-acre landscaped area officially opened in 1890 on top of a pile of garbage and manure landfill that had been carefully prepared by the prisoners. Four years later, thanks to the efforts of the zoo's founder, Daniel Lamb, a city alderman and local resident, the city had acquired two wolves and a small herd of deer for public display. These would be the first pieces in a gigantic collection.

The creatures first went on display in 1899 in small purpose-built enclosures. As you might imagine, the conditions were fairly bleak. Zoos in the Victorian period were more like curiosity shows than anything we'd be familiar with today and many of the animals were kept in pens that were patently too small but had the benefit of affording the best views for visitors.

The creatures first went on display in 1899 in small purpose-built enclosures. As you might imagine, the conditions were fairly bleak. Zoos in the Victorian period were more like curiosity shows than anything we'd be familiar with today and many of the animals were kept in pens that were patently too small but had the benefit of affording the best views for visitors.

Reading the Toronto Star, it's clear the zoo experienced an overwhelming amount of animal donations. A headline printed in March 13, 1902, reads "The Elephant Coming." Animal dealers working under the direction of Alderman Lamb had arranged for shipment of a second Indian elephant from Bombay via New York. Two lions were added to the same request.

The city's newest pachyderm was given the title "Princess Rita" on her arrival in Toronto. Zoo officials, who were often a mix of parks staff and inmates at the Don Jail serving time for minor crimes like vagrancy, taught Rita to carry people on her head. One of her first excursions was a wobbly ride down the public road to the Winchester Street bridge. "She has developed an awkward habit of lying down and rolling over when her load gets troublesome," the paper noted.

The new lions weren't as happy in their new surroundings. One of them caught a cold and "snarled at everything from his straw bed to a red-headed boy in the throng of visitors." Alderman Lamb, still involved in the day-to-day management, fed him cod liver oil, and it appears to have recovered.

The new lions weren't as happy in their new surroundings. One of them caught a cold and "snarled at everything from his straw bed to a red-headed boy in the throng of visitors." Alderman Lamb, still involved in the day-to-day management, fed him cod liver oil, and it appears to have recovered.

Without modern vets, the mortality rate among shipped animals was extremely high and there was always a risk the creatures wouldn't reach their destination. One steamship, the Buerania, carrying animals destined for the circus, lost three elephants, 100 monkeys, 26 "boxes of snakes," and hundreds of birds in a single voyage.

In 1902, the inventory at Riverdale included sixteen pheasants, two ocelots, a male camel, a dromedary, a bull buffalo, six pens of monkeys, a Siberian bear, a crane, lions, and a hippo. George H. Rust-D'Eye in Cabbagetown Remembered says 20,000 people crammed into the zoo the first weekend the elephant and lions went on display.

That same year the Moorish-inspired Donnybrook building was built and using funds from the Toronto Railway Company. During its construction one of the zoo's hippos sat down on a wet cement floor, leaving behind a substantial divot. The building is one of the few structures that still remains at Riverdale today.

Riverdale Zoo relied heavily on private donations to keep its herd expanding. Rattesnakes, Rocky Mountain badgers, porcupines, and a tiger were offered "almost faster than cages can be built for them." One aged lion, apparently a burden to management, "still fools the public by refusing to die" and free up enclosure space, it was reported.

It would be unfair to say there were no objections to the way animals were handled at the zoo. The Humane Society complained about the elephants being "shackled by one leg" in small enclosures. The cold weather posed challenges too. A winter house protected the most vulnerable creatures and radiators were installed in some cages as a measure of protection against the elements.

It would be unfair to say there were no objections to the way animals were handled at the zoo. The Humane Society complained about the elephants being "shackled by one leg" in small enclosures. The cold weather posed challenges too. A winter house protected the most vulnerable creatures and radiators were installed in some cages as a measure of protection against the elements.

The animals took their revenge when they could. In 1905 a bull buffalo protecting its cow and calf charged at a group of workers, sending them scrambling up trees. The group was trapped for half an hour before someone could distract the beast long enough for them to climb down.

Monkey teasing was another popular pastime for visitors. Everything from cigars to ice cream would be passed through the bars to the excitable little critters, and they occasionally snapped at stray fingers. One provoked elk was so frustrated by a group of visiting boys that it mortally gored its mate. Dr. Mole, the aptly named veterinarian, was forced to euthanize the wounded beast.

In another bizarre incident, the resident pelican had 15-inches its beak bitten off at the wolf enclosure during a ill-advised visit. Unpeturbed, a doctor from the cat and dog hospital successfully grafted a duck's bill to the bird using horsehair. It seemed to work, and the animal was able to eat diced fish normally.

In another bizarre incident, the resident pelican had 15-inches its beak bitten off at the wolf enclosure during a ill-advised visit. Unpeturbed, a doctor from the cat and dog hospital successfully grafted a duck's bill to the bird using horsehair. It seemed to work, and the animal was able to eat diced fish normally.

"Indeed, the pelican's bill will be stronger than ever," the Star reported. "It will combine the weapon of the duck with its own liberal organ."

Perhaps the most shocking example of Frankenstein engineering almost occurred in 1918. The early morning bellows of the zoo's sea lion had become a nuisance to local neighbours, so superintendent Frank Goode proposed a solution: surgically remove its vocal chords. "If we can give Torontonians a sea lion without a noise we will do it," he said.

Perhaps the most shocking example of Frankenstein engineering almost occurred in 1918. The early morning bellows of the zoo's sea lion had become a nuisance to local neighbours, so superintendent Frank Goode proposed a solution: surgically remove its vocal chords. "If we can give Torontonians a sea lion without a noise we will do it," he said.

It's not clear from the wording in the police blotter, but it appears one Sunday when the animal was mercifully silent a man named Tully Naumoff appears to have been arrested in the park and fined $5 plus costs for mimicking the barking sounds normally heard from the animal's cage "for the ladies."

Thankfully, the Humane Society were just as vociferous, and the animal was saved from the surgeons scalpel by the acting parks commissioner.

Conditions improved at Riverdale over the decades but by the 1960s the tiny cages and concrete outdoor runs were hopelessly out of date. On completion of the new Metropolitan Toronto Zoo, Riverdale closed for the last time at sunset on June 30, 1975, and much of the buildings were torn down.

Conditions improved at Riverdale over the decades but by the 1960s the tiny cages and concrete outdoor runs were hopelessly out of date. On completion of the new Metropolitan Toronto Zoo, Riverdale closed for the last time at sunset on June 30, 1975, and much of the buildings were torn down.

Riverdale Farm, the successor to the zoo, opened in 1978, specializing in rare breeds of regular farm animals. No sea lions, thankfully.

FURTHER READING:

MORE IMAGES

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Image: City of Toronto Archives