When Toronto's lights went out earlier this summer following a torrential rainstorm, thousands of people got a short and unwanted sample what life was like in the late 19th century before the Toronto Electric Light Company brought light and electricity to our lives.

When Toronto's lights went out earlier this summer following a torrential rainstorm, thousands of people got a short and unwanted sample what life was like in the late 19th century before the Toronto Electric Light Company brought light and electricity to our lives.

The company, all-powerful for most of its brief existence, set up the first crackling interior lights in the buildings around King and Yonge, demonstrated the technology used on today's subway and streetcars before either was commonplace at the Industrial Exhibition, and even introduced Victorian Toronto to the vibrator (well, sort of) in one of its catalogues.

This is how Toronto emerged from the shadows thanks to the pioneering efforts of its first electricity company and its leading light, J. J. Wright.

McConkey's Restaurant at 145 Yonge Street holds the distinction for being the first Toronto property to be lit by electrical power. In an 1879 demonstration and promotional stunt, a noisy steam engine chugged to life, turned a basic dynamo, and bathed the fashionable eatery's tables in a warm orange light. To celebrate the feat, McConkey's served free ice cream to the gathered crowd.

McConkey's Restaurant at 145 Yonge Street holds the distinction for being the first Toronto property to be lit by electrical power. In an 1879 demonstration and promotional stunt, a noisy steam engine chugged to life, turned a basic dynamo, and bathed the fashionable eatery's tables in a warm orange light. To celebrate the feat, McConkey's served free ice cream to the gathered crowd.

Electricity was rare in the late 1870s, but it wasn't a total novelty in Toronto - it had been employed years earlier for sending telegraphs and powering telephone lines. Without a generator or a central supply network, the messaging companies, including the Toronto Telephone Despatch Co., the producers of the city's first phone book, relied on simple batteries.

Electricity was rare in the late 1870s, but it wasn't a total novelty in Toronto - it had been employed years earlier for sending telegraphs and powering telephone lines. Without a generator or a central supply network, the messaging companies, including the Toronto Telephone Despatch Co., the producers of the city's first phone book, relied on simple batteries.

A few years later, in 1881, John Joseph Wright built the first Canadian-made generator in a spare room at his father-in-law's box factory on King just west of Berkeley. Wright, "a stocky man with a pleasantly square face, flowing moustache, and keen inquisitive eyes," according to historian Robert M. Stamp, had studied in the U.S. the principles of electricity and helped set up America's first arc street lamp at Public Square in Cleveland, Ohio.

Arc lamps, patented in 1846 and first used commercially at the South Foreland Lighthouse near Dover, U.K. in 1858, generate light by jumping a high-voltage spark of electricity between two carbon rods inside a gas-filled glass bulb. Until shortly after 1900, arcing an electrical current was the only way to produce a practical light.

Arc lamps, patented in 1846 and first used commercially at the South Foreland Lighthouse near Dover, U.K. in 1858, generate light by jumping a high-voltage spark of electricity between two carbon rods inside a gas-filled glass bulb. Until shortly after 1900, arcing an electrical current was the only way to produce a practical light.

Wright installed his generator near King and Yonge and sold the piercing light of the early bulbs to Eaton's department store and a handful of other local businesses keen to appear technologically advanced. In doing so, Wright became the first person to generate and sell electricity commercially in Toronto.

As Stamp notes in Bright Lights, Big City, his excellent history of electricity in Toronto, early adopters experienced plenty of teething issues with their new hook-ups. A coffee shop that wired its grinder directly to the power supply (no outlets yet) found their machine took on a life of its own, speeding up to an uncontrollable speed and firing coffee across the room. It was eventually stopped when the motor short-circuited.

As Stamp notes in Bright Lights, Big City, his excellent history of electricity in Toronto, early adopters experienced plenty of teething issues with their new hook-ups. A coffee shop that wired its grinder directly to the power supply (no outlets yet) found their machine took on a life of its own, speeding up to an uncontrollable speed and firing coffee across the room. It was eventually stopped when the motor short-circuited.

Moments of confused hilarity aside, Wright did more than anyone else to bring electricity to the people of Toronto. He lit the Industrial Exhibition, a forerunner to the CNE, with a set of arc lights in 1882 and built Canada's first electric railway there the year after.

The train, with flat cars and a basic locomotive, ran on a straight track from Strachan to Dufferin and was powered by an electrified third rail, the same system used on the subway today. The year after, in 1884, Wright enlisted the help of Charles Van Depoele, a pioneer in his own right, and adapted the train to draw power from an overhead wire, like modern streetcars.

The train, with flat cars and a basic locomotive, ran on a straight track from Strachan to Dufferin and was powered by an electrified third rail, the same system used on the subway today. The year after, in 1884, Wright enlisted the help of Charles Van Depoele, a pioneer in his own right, and adapted the train to draw power from an overhead wire, like modern streetcars.

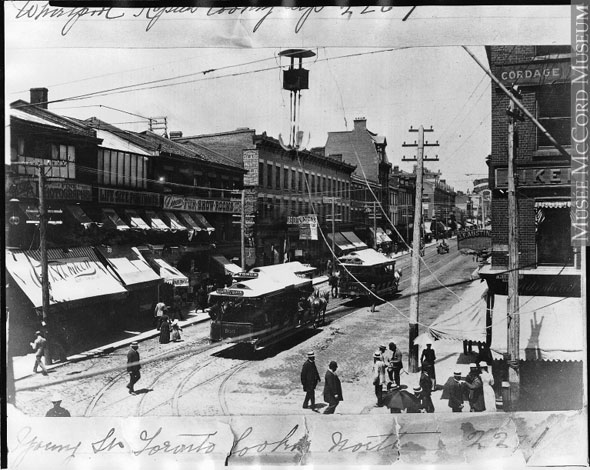

Lighting the streets would be Wright's next challenge, though by the middle part of the 1880s the competition was beginning to mount. Arc lights were already casting their weird glow the four corners of King and Yonge streets at night. One R. H. Lunt had been given permission by city council to hang lights from fire alarm poles, though the major street lighting contract was still held by the Consumers' Gas Company.

Before Wright and his rivals, Toronto's streets were lit by gas lamp, if they were illuminated at all. On quiet residential roads and down laneways the city was still an inky blackness after sundown. Most homes were lit by gas lamp or candles, which didn't provide much illumination at all. A decent candle was about 100 times dimmer than a standard 100w bulb today.

J. J. Wright's generating station bounced around between various factories on Sherbourne Street before he founded the Toronto Electric Light Company and found a permanent home for the equipment at the foot of Scott Street, just south of the Esplanade.

J. J. Wright's generating station bounced around between various factories on Sherbourne Street before he founded the Toronto Electric Light Company and found a permanent home for the equipment at the foot of Scott Street, just south of the Esplanade.

By now three companies were vying for the lucrative and soon-to-be-available city lighting contract: naturally, the long-established Consumers' Gas Company lobbied to maintain the status quo, but the Toronto Electric Light Company and its rival the Canadian Electric Light Manufacturing Company were pushing for a system of arc lights.

In the spirit of compromise, or perhaps because they couldn't decide how things would work out, council opted for a mix of gas and electric lights. TELCO, as it often styled itself, installed fifty lights on Queen, King, and Yonge as the Electric Light Manufacturing Company fell by the wayside.

Wright's ability to make good on the street lighting contract was thanks in large part to a major investment by a group of businessmen led by Henry Pellatt, a renowned stockbroker who would later build Casa Loma. The group's cash gave Wright the ability to upgrade the equipment at the Scott St. plant.

Wright's ability to make good on the street lighting contract was thanks in large part to a major investment by a group of businessmen led by Henry Pellatt, a renowned stockbroker who would later build Casa Loma. The group's cash gave Wright the ability to upgrade the equipment at the Scott St. plant.

The Romanesque Revival brick building nudged out in to the water of the Toronto Bay from its lakefront perch and contained ten 100-horsepower boilers connected to various engines and belt-driven dynamos. The crackling electricity was distributed via a tangled network of overhead wires, along the city's streets.

For the most part, the Toronto Electric Light Company focused on outdoor lighting and powering streetcars. The Toronto Incandescent Electric Light Company (TIELCO,) a later arrival which held the Canadian patents to several Thomas Edison lighting patents, cornered the domestic market for several years before it was eventually bought by TELCO.

The group of leaders from the two major electricity companies and the city's early transit system was informally known as "The Syndicate." Frederic Nicholls, the founder of TIELCO bought technical nous, William Mackenzie owned the precursor to the TTC, the Toronto Street Railway, and Henry Pellatt had the business acumen to tie it all together.

Around this time, with a foothold in the household electrical market, the Toronto Electric Light Company published a glossy brochure advertising the various high-tech products that "small families that keep no servant" could use with their new electricity supply.

Around this time, with a foothold in the household electrical market, the Toronto Electric Light Company published a glossy brochure advertising the various high-tech products that "small families that keep no servant" could use with their new electricity supply.

Titled "Electricity in the Home," the booklet showed off an electric iron, toaster, waffle iron, coffee urn, cereal cooker, chafing dish, cooking range, vacuum cleaner, and even "vibrator."

"The Electric Vibrator is a very essential article in 'my lady's' boudoir," the caption reads. "By its use, vibratory treatment may be applied at one's own convenience." Perhaps a little disappointingly, the device was shaped like a hairdryer with a small jackhammer attachment at the end and was for facial use.

The Syndicate and TELCO continued to strengthen their position as the turn of the century passed. In 1903, the company built a hydro-electric power station on the Niagara River and the first volts of outside power reached a TELCO distribution centre on Davenport Road three years later.

The Syndicate and TELCO continued to strengthen their position as the turn of the century passed. In 1903, the company built a hydro-electric power station on the Niagara River and the first volts of outside power reached a TELCO distribution centre on Davenport Road three years later.

With other company's nipping at its heels, the Toronto Electric Light Company soon found itself in a power struggle with Ontario's own publicly-owned electricity provider, the Hydro-Electric Power Commission. A 1908 referendum threw support behind the provincial electricity supply, and in 1911 the HEPC's own Niagara hydro supply was ceremonially switched on during a special ceremony at Old City Hall in front of 30-50,000 people.

As historian Stamp recalls, a giant diorama of Niagara Falls was used as a backdrop for the event and at the crucial moment of illumination water was meant to cascade over the top, bringing it to life Unfortunately, the flow was a little stronger than expected and several invited dignitaries were soaked by the spray.

The Toronto Hydro-Electric System would evolve into Toronto Hydro but not before embarking on an aggressive plan to drive the likes of the Toronto Electric Light Company out of business. THES slashed rates and mounted an advertising strategy that was so successful by 1917 two-thirds of the city had defected away from the city's first electricity provider.

The Toronto Hydro-Electric System would evolve into Toronto Hydro but not before embarking on an aggressive plan to drive the likes of the Toronto Electric Light Company out of business. THES slashed rates and mounted an advertising strategy that was so successful by 1917 two-thirds of the city had defected away from the city's first electricity provider.

The strangulation of TELCO didn't entirely go to plan - several embarrassing equipment failures in the years leading up to the first world war forced THES to buy power from its rival in order to maintain its own supply.

The Toronto Electric Light Company shone its last in the early 1920s when the last of its civic contracts expired. The brick Scott St. plant was eventually torn down and the city moved on with its electrical consumption. Today, Toronto Hydro serves 709,000 customers and supplies around 20% of the province's electrical power.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: City of Toronto Archives, Toronto Public Library, McCord Museum,