Shuttling along the QEW towards Toronto and the newly opened Gardiner Expressway in the late 1950s, one would get his first good view of the skyline at around Park Lawn Avenue. As you took in the positively Buffalo-esque vista, marked by sepia-toned banks and hotels hovering over still prominent church steeples, the foreground would be dotted with a series of picturesque motels spread across Lake Shore Boulevard. Clinging to Humber Bay, this strip of lakeside properties brimmed with confidence, promising the transitional comforts of television, in-ground (but naturally unheated) pools, and stunning views of a city that had yet to embrace fun. Sunnyside had been razed, but you could still vacation in sight of the city.

Shuttling along the QEW towards Toronto and the newly opened Gardiner Expressway in the late 1950s, one would get his first good view of the skyline at around Park Lawn Avenue. As you took in the positively Buffalo-esque vista, marked by sepia-toned banks and hotels hovering over still prominent church steeples, the foreground would be dotted with a series of picturesque motels spread across Lake Shore Boulevard. Clinging to Humber Bay, this strip of lakeside properties brimmed with confidence, promising the transitional comforts of television, in-ground (but naturally unheated) pools, and stunning views of a city that had yet to embrace fun. Sunnyside had been razed, but you could still vacation in sight of the city.

This was middle class paradise, and it would last for another two decades before the suburban building boom, the ubiquity of the backyard pool, and cheap air travel snuffed out the novelty of inexpensive lakeside accommodation. From the mid 1980s on, Toronto's motel strips on Lake Shore Blvd. and Kingston Rd. progressively ceased to offer resort-like charm, offering in its place cautious shelter for the down on their luck and, later, newcomers to the city. The history of these places is as complicated as their floor plans are simple. Only a handful of the Scarborough motels remain, living relics that are bound to run out the string before development renders them extinct.

It's not surprising that the Toronto Archives digital holdings pay little due to the humble motel. Where the hotel is urban, the motel is necessarily located on the periphery, nearer to nature, never central, and always defined by a certain impermanence. Where the hotel is luxurious, the motel is leisurely. The genealogy of these low rise structures is pastoral to the core.

These were and are places that warn against staying inside for too long (you must visit the pool) and discourage long stays (you get a TV but not a kitchenette). No, the motel offers cautious refuge and utter simplicity. "All I need is a bed, a bathroom, a telephone, and sometimes a television in the unlikely event that one day I'll get a chance to knock off early," Agent Cooper tells Sheriff Truman in the Twin Peaks pilot, summing up perfectly what these transitional spaces offer.

Closer to home, this impermanence is captured in the names of old motels. Unlike the stately titles of iconic hotels like The Queen's Hotel, The Royal York, The Dominion or even Sutton Place, with motels you're more likely to encounter temporary and situational monikers like Have-A-Nap, The Rainbow, The Hillcrest, The Beach, and The Shore Breeze, to offer only a few local examples of this nomenclature. It's as if a certain ephemeral quality is the very condition of possibility for these places.

Which is why it makes sense that they're dying out. The growth of the city - prefigured all the way back when the Gardiner was built - has consumed these little enclaves of recreation. Now our escapes take us further away from home, Lake Ontario lacks the allure it once had, and vacancy signs are met with matching looks.

PHOTOS

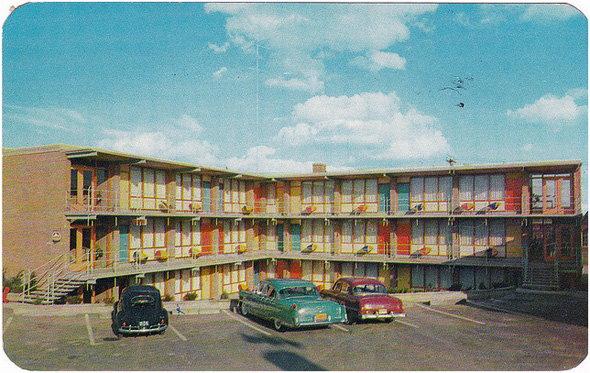

Lake Shore Blvd. motel strip, 1960s

Lake Shore Blvd. motel strip, 1960s

Lido Motel, Kingston Rd. (still open)

Lido Motel, Kingston Rd. (still open)

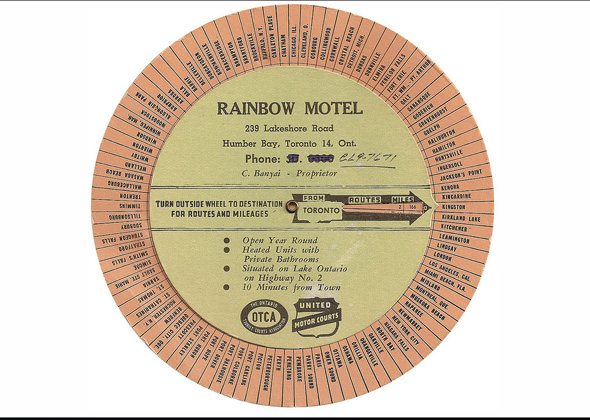

Rainbow Motel (Lake Shore Blvd.)

Rainbow Motel (Lake Shore Blvd.)

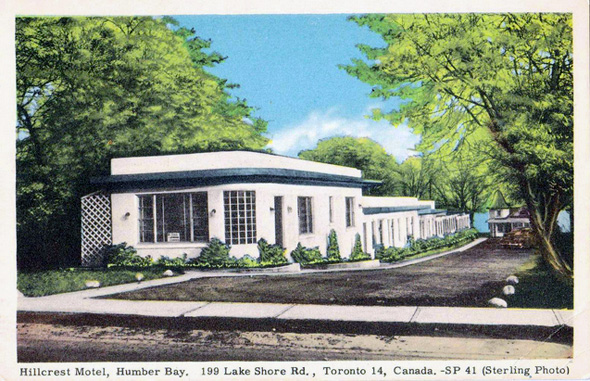

Hillcrest Motel, Lake Shore Blvd.

Hillcrest Motel, Lake Shore Blvd.

Ditto

Ditto

Seaway Motel, Lake Shore Blvd.

Seaway Motel, Lake Shore Blvd.

Ditto

Ditto

Park Motel, Kingston Rd. (still open)

Park Motel, Kingston Rd. (still open)

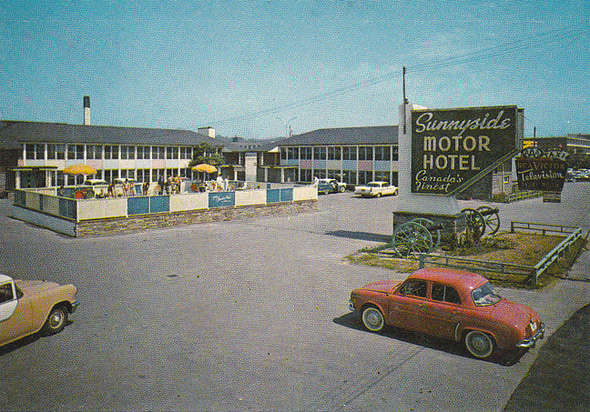

Sunnyside Motor Hotel, Lake Shore Blvd.

Sunnyside Motor Hotel, Lake Shore Blvd.

Ditto

Ditto

Avon Motel, Kingston Rd. (still open)

Avon Motel, Kingston Rd. (still open)

Andrews Motel, Kingston Rd.

Andrews Motel, Kingston Rd.

In 1983, Toronto photographer Patrick Cummins captured the Lake Shore motel strip, which was already in a state of decline. The photos below are selections from his valuable work documenting this lost bits of Toronto history.

Beach Motel

Beach Motel

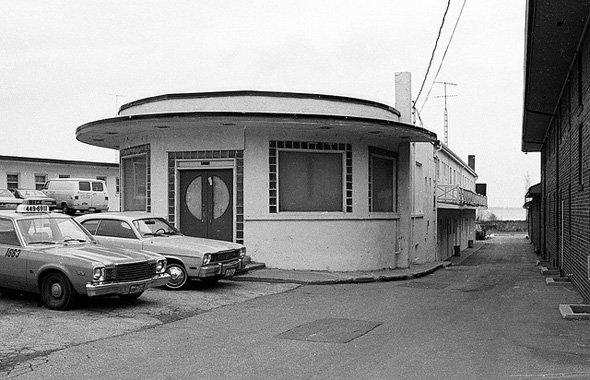

Westpoint Motor Hotel & Restaurant

Westpoint Motor Hotel & Restaurant

Alternate angle

Alternate angle

Eagle's Nest Motel

Eagle's Nest Motel

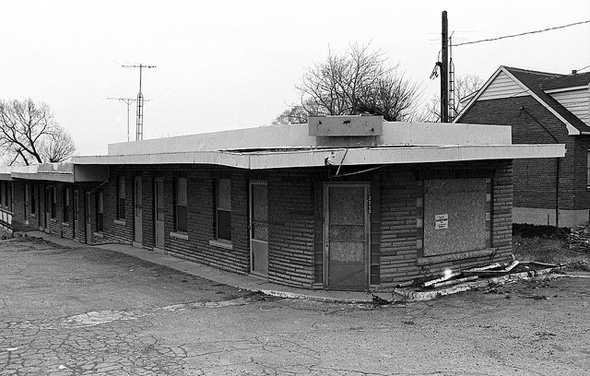

Cumberland Motel

Cumberland Motel

Shady Beach Motel

Shady Beach Motel

Alternate Angle

Alternate Angle

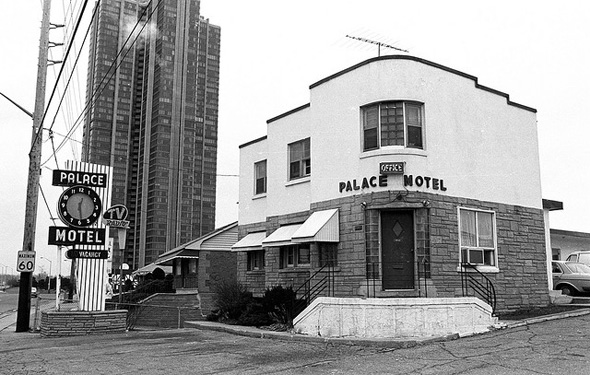

Palace Motel

Palace Motel

Alternate angle

Alternate angle

Silver Moon Motel

Silver Moon Motel