Paying to use Highway 407 might seem like a drag, less so if you have one of those electronic windshield devices, but imagine having to cough up on every journey on every major road in or out of the city.

Paying to use Highway 407 might seem like a drag, less so if you have one of those electronic windshield devices, but imagine having to cough up on every journey on every major road in or out of the city.

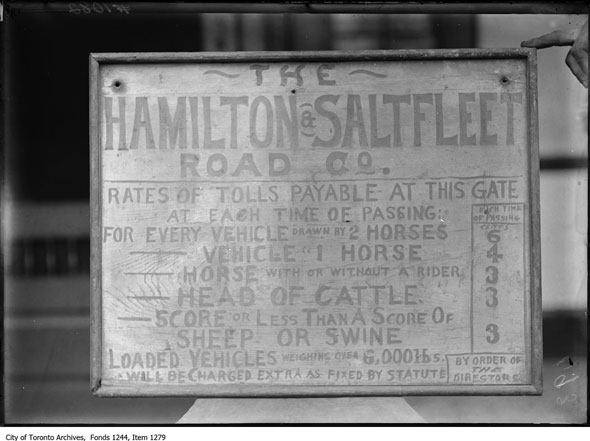

Prior to 1895, York County, the dissolved subregion of which Toronto was once the principal town, charged road users a fee for each passage through a series of gates set up at key positions around the city. The money was gathered by the county and used to maintain and expand the road network, which was often surfaced with planks and in need of constant upkeep.

Later, private companies were invited to bid on road building contracts and recoup construction costs through tolls, but this scheme also fell by the wayside as Toronto moved away from directly charging travellers.

This month marks the 113th anniversary of the original abolition of toll gates in Toronto.

In the 1800s, toll booths were positioned on every major route out of town. At various times, little wooden cottages with a large gate blocking the road could be found at King and Yonge, Queen and Bathurst (then part of Dundas,) Dundas and Bloor, and Broadview and Danforth, to name a few.

In the 1800s, toll booths were positioned on every major route out of town. At various times, little wooden cottages with a large gate blocking the road could be found at King and Yonge, Queen and Bathurst (then part of Dundas,) Dundas and Bloor, and Broadview and Danforth, to name a few.

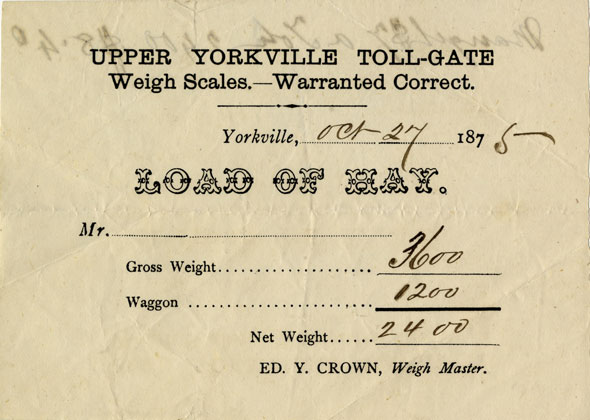

Then as now, paying for passage was an unpopular proposition, especially for the drivers of delivery wagons visiting Fort York and the St. Lawrence Market, two major institutions in early Toronto. The cost varied by route, the type of load, the amount on the wagons, and the reason for passing.

At Dundas and Jane, it cost a penny to pass in a vehicle drawn by a single horse. Two horses pulling a carriage attracted a fee of a penny and a half. There were half penny tolls for herds of 20 or more animals or for a horse and rider. In other locations, weigh scales were used to measure the amount of material traveling in or out of the city.

Funeral processions, Sunday church goers, and military vehicles were exempt.

As Adam Bunch writes in Spacing, disgruntled drivers would occasionally speed up and blow through (or over) the closed toll gate. Others, however, took the practice of avoiding fees much more seriously.

As Adam Bunch writes in Spacing, disgruntled drivers would occasionally speed up and blow through (or over) the closed toll gate. Others, however, took the practice of avoiding fees much more seriously.

In 1895, while York County was still deciding whether to nix tolls entirely, a group of men burned down a set of wooden toll gates on Yonge Street. The city's response was to propose a set of fire-proof iron gates. "One councillor observed that corrugated iron would be the best because when toll-gates were abolished the place could be used as a public lavatory," the Toronto Star recorded.

Decades earlier, a lumber dealer reportedly found a more creative solution. The story goes that after a series of altercations with the operators of a toll gate at Queen and Ossington, some of them physical, an unnamed supplier to Fort York bought the land on the northeast corner of the intersection, directly opposite the gate.

Decades earlier, a lumber dealer reportedly found a more creative solution. The story goes that after a series of altercations with the operators of a toll gate at Queen and Ossington, some of them physical, an unnamed supplier to Fort York bought the land on the northeast corner of the intersection, directly opposite the gate.

On the property he laid out Rebecca Street, historian John Ross Robertson recalls in his book Landmarks, a short road that bypassed the pay point. The name came from the Rebeccaites, a group of 19th century Welsh rebels who, dressed as women, burned and demolished toll gates in Britain as symbols of unfair taxation.

Unfortunately, the story is a little dubious. There's evidence the road was only given its current name (it was called Dever's Lane first) after the toll booth had disappeared.

As it turned out, York County didn't have to rebuild the torched Yonge Street gates - the decision to permanently eliminate tolls came on December 30, 1895. Market fees were removed at the same time, allowing traders from outside the city to sell at the St. Lawrence Market with fewer levies.

One of the city's few remaining toll booths - Tollgate #3 - still stands away from its original location close to Bathurst and Davenport. The house is of exceedingly rare plank construction - only one other is known to exist in Ontario - and has been picked up and moved several times, once spending time in storage at the TTC yard.

One of the city's few remaining toll booths - Tollgate #3 - still stands away from its original location close to Bathurst and Davenport. The house is of exceedingly rare plank construction - only one other is known to exist in Ontario - and has been picked up and moved several times, once spending time in storage at the TTC yard.

Amazingly, knowledge of the building's history was virtually unknown until 1993, when it was saved from destruction by developers and moved a final time to its present location.

It's now open as a museum at Bathurst and Davenport in Tollkeeper's Park.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: Toronto Public Library, City of Toronto Archives