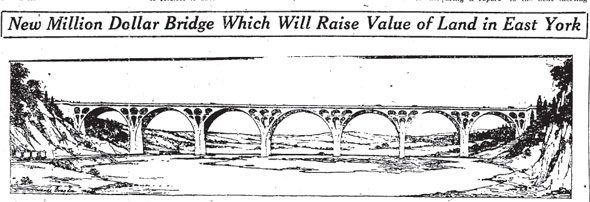

The Leaside Viaduct doesn't get nearly the attention it deserves. Needlessly dwarfed in terms of fame and stature by its slightly older cousin to the south, the Prince Edward Viaduct, the Leaside bridge is worthy of celebration all by itself.

The Leaside Viaduct doesn't get nearly the attention it deserves. Needlessly dwarfed in terms of fame and stature by its slightly older cousin to the south, the Prince Edward Viaduct, the Leaside bridge is worthy of celebration all by itself.

The simple, utilitarian superstructure and basic concrete piers were built in world record time using construction techniques never before seen in Canada. It took barely 10 months to connect the top of Pape Ave. with the burgeoning community of Leaside and its thrumming racetrack.

For comparison, the Bloor Viaduct, which was rewarded with an official royal title and featured as the central location for the popular novel In the Skin of a Lion, took almost five times as long to build.

The need for a second road bridge to span the Don Valley became apparent in the late 1920s as the little neighbourhood of Leaside, a planned community partially laid out to plans by Frederick Gage Todd for the Canadian Northern Railway, was threatening to boom into a fully-fledged town.

The need for a second road bridge to span the Don Valley became apparent in the late 1920s as the little neighbourhood of Leaside, a planned community partially laid out to plans by Frederick Gage Todd for the Canadian Northern Railway, was threatening to boom into a fully-fledged town.

Leaside is named for John Lea, an early farm owner in the area. "Leaside" was the name John's son, William, gave to a brick farmhouse he built on the property, which was then acres of apple orchard and pasture, in the 1850s. CNR entered the Leaside story in 1912 when William Lea sold part of his property to allow for a rail right of way an repair shops.

CNR upped the ante by promising an entire new model town for its Leaside workers. Early plans called for a tidy collection of winding residential streets and wider arterial avenues dotted with parks and commercial strips. As Jamie Bradburn notes over at Torontoist, the town was designed to be home to at least 30,000 residents with an eye to being annexed by the City of Toronto.

Unfortunately, it didn't entirely go to plan. Leaside was built partially to Todd's blueprint but the predicted population growth was slow to materialize. In 1927, more than 15 years after its creation, the Toronto Star was still predicting that Leaside would become "in the near future a thriving town of 25,000 population, not the product of a hysterical real estate boom, but the natural corollary of civic development."

One of the issues holding Leaside back was its location. The town was in a "condition of splendid isolation" on the far side of the Don Valley, largely cut off from major roads. If the fledgling town was to realize its potential, it needed a link to the outside world.

Unlike the Prince Edward Viaduct, the Leaside Viaduct didn't need a series of referendums to gain final approval. A link to the rabidly popular Thorncliffe Park Raceway, a mecca for thoroughbred and harness racing and the spiritual home of the Prince of Wales Stakes, was enough, it seems.

Unlike the Prince Edward Viaduct, the Leaside Viaduct didn't need a series of referendums to gain final approval. A link to the rabidly popular Thorncliffe Park Raceway, a mecca for thoroughbred and harness racing and the spiritual home of the Prince of Wales Stakes, was enough, it seems.

Construction began in earnest on Jan. 2, 1927, a few weeks after the official groundbreaking on Dec. 13, 1926. The earth on the south side of the valley was already frozen in an unyielding mass so a fire was burned over the ceremonial first patch of sod, which was turned by East York Reeve Robert Henry McGregor using a miniature silver shovel.

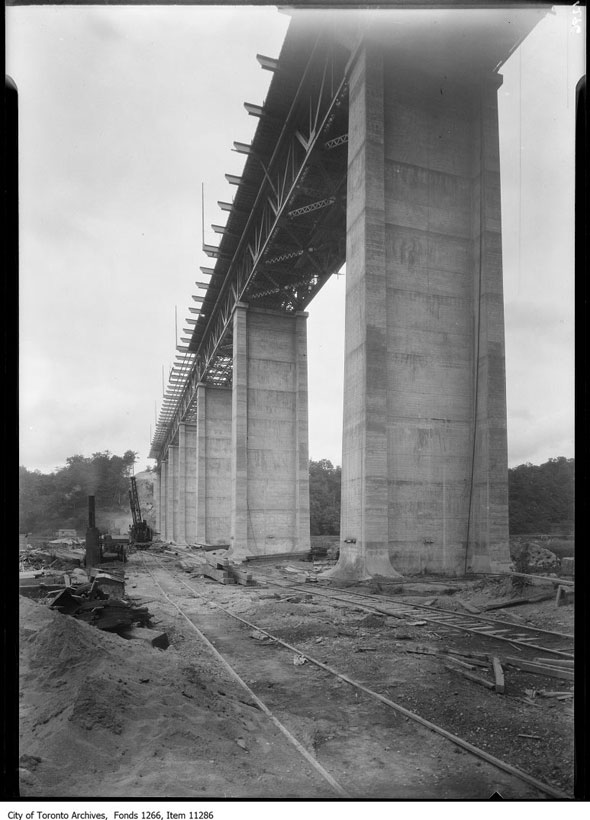

In the valley below, amid eight centimetres of snow, workmen were laying the tracks for the temporary railway that would haul concrete and metalwork for the new bridge. It was the first time a major construction project had commenced in Toronto with snow on the ground, and more in the forecast.

The construction schedule was ambitions. Designer and lead engineer Frank Barber pledged to deliver the $150,000 concrete and steel structure, substantially different to the one initially approved by the local councils, within a year - an unprecedented timeframe.

The construction schedule was ambitions. Designer and lead engineer Frank Barber pledged to deliver the $150,000 concrete and steel structure, substantially different to the one initially approved by the local councils, within a year - an unprecedented timeframe.

Several new innovations made the goal achievable. Barber and his team would measure the dry ingredients for the concrete supports by weight, reducing waste, while the steel superstructure would be built between the concrete piers without scaffolds or temporary supports, borrowing a system used during construction of the Quebec Bridge.

Barber's teams worked 24 hours January to March through bitter cold, wind, and snow. Massive searchlights on the valley floor bathed the gigantic structure in brilliant light after dark. An average of 4 metres of concrete was laid every four hours, Roger Miller and Sons, the contractors, told the papers.

The extreme haste had consequences. Three men died while working on the bridge, but Barber believed a few mishaps were to be expected. "This is not an usual number because you cannot get a gang of several hundred men working on a construction of such a size without an occasional accident happening," he said.

The extreme haste had consequences. Three men died while working on the bridge, but Barber believed a few mishaps were to be expected. "This is not an usual number because you cannot get a gang of several hundred men working on a construction of such a size without an occasional accident happening," he said.

With few setbacks (apart from the occasional low-profile personal tragedy,) the Leaside Viaduct was complete by late October 1927, barely 10 months after the groundbreaking ceremony. The speed of construction set a world record and the final bill came in slightly over budget at $975,000 - about $13 million in today's money.

The Star called 427-metre long structure "one of the greatest links that has been forged for the development of the Queen City and suburbs in the last score of years." Leaside and East York decided to name the span, decorated with few architectural flourishes, Confederation Viaduct. It was 60 years since the founding of Canada.

At exactly 3 p.m. on Oct. 29, 1927, William Donald Ross, Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, cut the ribbon strung across the entrance to the south side of the bridge using a pair of specially engraved scissors. The band of the Mississauga Horse played God Save the King and a score of dignitaries gave speeches.

The first vehicles to cross the concrete surface were a TTC bus, the first on the new Pape route, and a bread wagon bound for Leaside. "The East York-Leaside Viaduct changes the whole strategical position of Leaside," The Star wrote. "It centralizes the town and puts it on one of the most important highways in the metropolitan district of Toronto."

The first vehicles to cross the concrete surface were a TTC bus, the first on the new Pape route, and a bread wagon bound for Leaside. "The East York-Leaside Viaduct changes the whole strategical position of Leaside," The Star wrote. "It centralizes the town and puts it on one of the most important highways in the metropolitan district of Toronto."

The deck was widened to support six lanes of vehicle traffic in 1969 as the city mulled extending Leslie St. south across the bridge. A major facelift and heritage status arrived in 2004.

Like its cousin to the south, the height of the Leaside Viaduct has made it a magnet for suicide since at least the 1930s. It lacks the protection provided by the Luminous Veil on the Bloor Viaduct and as Graeme Bayliss writes in his excellent and powerful story on the subject in the Fall issue of Spacing, there are no plans to build a barrier.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Image: City of Toronto Archives