In an parallel universe, Toronto is home to a pioneering offshore community with canals instead of streets. The CN Tower looks weird - it's probably not even called that - and most of the central waterfront is consumed by a complex that includes a massive CBC headquarters and a reworked Front Street.

In an parallel universe, Toronto is home to a pioneering offshore community with canals instead of streets. The CN Tower looks weird - it's probably not even called that - and most of the central waterfront is consumed by a complex that includes a massive CBC headquarters and a reworked Front Street.

There are grand avenues and wide European-style traffic circles, the Eaton Centre doesn't exist, and the tallest building in the city is a bizarre semi-transparent affair at College and Yonge. A commemorative plaque at its base recalls the long lost Eaton's College Street store, which was knocked down to make way for the massive structure.

Oh, and there might just have been a few more downtown subway stations.

None of these wonders came to pass, of course, but they all came tantalizingly close. With David Mirvish and Frank Gehry's King West mega condos currently going through the approval process (or dis-approval, as the case may be), here's a look back at several massive Toronto projects that never made it past the concept phase.

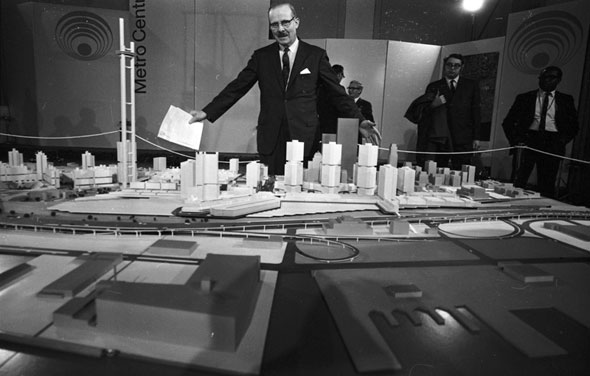

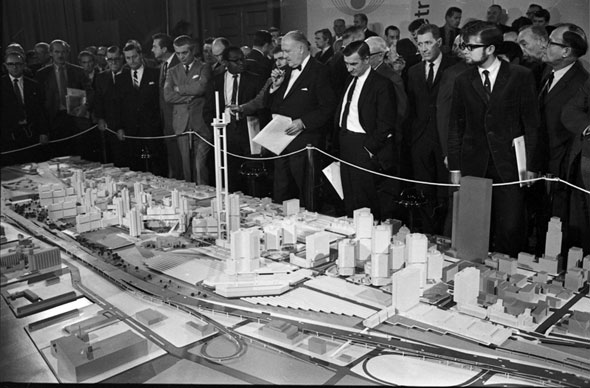

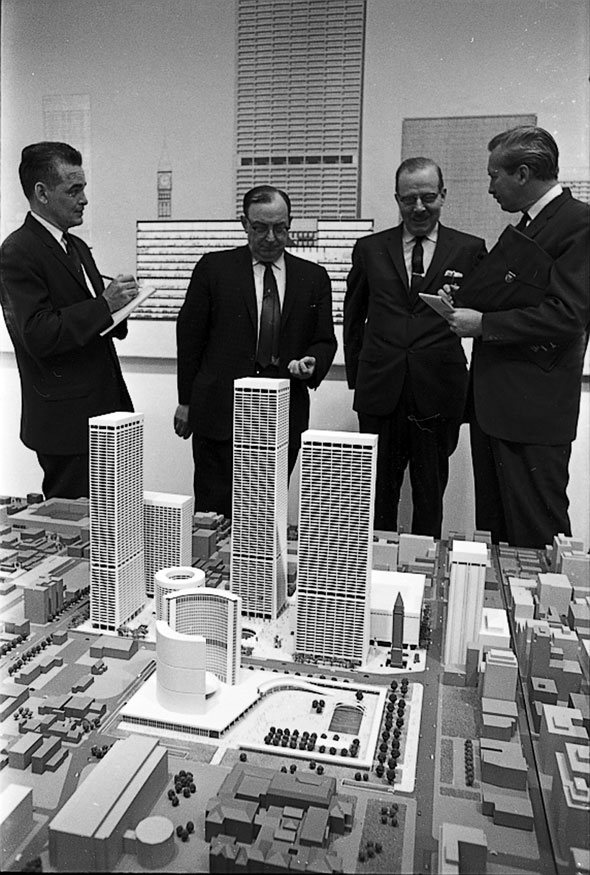

METRO CENTRE In the 1960s, faced with hundreds of acres of surplus railway lines, sidings, and train sheds, two of Canada's biggest rail companies were keen to cash in and develop their massive and increasingly valuable holdings.

In the 1960s, faced with hundreds of acres of surplus railway lines, sidings, and train sheds, two of Canada's biggest rail companies were keen to cash in and develop their massive and increasingly valuable holdings.

The Metro Centre proposal, the brainchild of Canadian Pacific and Canadian National, would have created a "city-within-a-city" between the Gardiner, Bathurst, Front, and Yonge. "4.5 million square feet of office space, 600,000 square feet of commercial space, and 9,300 residential units," Mark Osbaldeston says in his book Unbuilt Toronto.

The subway bend at Union Station would have been shifted south to Queens Quay, creating three new stops, a new transit hub for buses and trains would be built over the tracks, and there would be a new convention centre and English-language CBC broadcast centre.

Metro Centre got remarkably far: Metro Toronto, the now defunct senior level of government, gave its approval, as did the City of Toronto and its planners, but a group of concerned citizens successfully appealed the decisions at the Ontario Municipal Board, resulting in demands for additional parkland and smaller towers.

The mega project - the biggest ever pitched in North America - fizzled when the 1972 municipal election delivered a major idealogical shake-up at city council. The CN Tower, Roy Thomson Hall, and the Metro Toronto Convention Centre were the only pieces ever realized, albeit to different designs.

HARBOUR CITY Imagine living on the Toronto Islands. No, not those - the ones made out of infill just west of the disused airport runway.

Imagine living on the Toronto Islands. No, not those - the ones made out of infill just west of the disused airport runway.

Harbour City, the brainchild of the Toronto Harbour Commission, would have been an offshore community stitched together by canals and lagoons. The low-rise, mixed-use buildings, arranged in clusters, would provide living space for 60,000 people from a range of financial backgrounds. Urbanist Jane Jacobs was on board: "Harbour City is probably the most important advance in planning for cities that has been made this century," she said. What could go wrong?

The proposal would have closed Billy Bishop airport and moved it to the Port Lands (where it could handle extra capacity) and likely turned the Toronto Islands into a park. Harbour City wouldn't have been Venice North - a ring road would have provided vehicular access to the community from the foot of Bathurst Street.

Like Metro Centre and the Spadina Expressway, both still real prospects at the time, Harbour City was sunk by local opposition and a fortuitous change of government. In 1972, the feds decided its new international airport would be built in Pickering instead (still waiting) and the plans faded forever, which was probably for the best. The winters would have been hell.

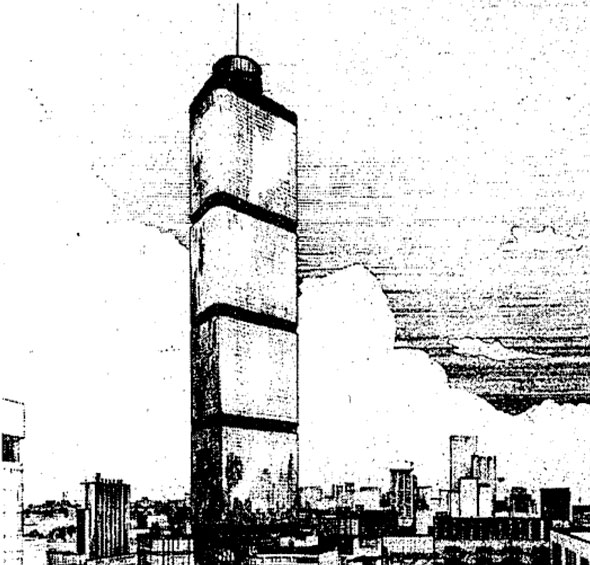

JOHN MARYON TOWER For several years, Eaton's management was earnestly devoted to knocking down its beautiful, historic Toronto stores for faceless office complexes. Case in point: John Maryon Tower, a proto-CN Tower that could have erased the company's College Street store in the early '70s.

For several years, Eaton's management was earnestly devoted to knocking down its beautiful, historic Toronto stores for faceless office complexes. Case in point: John Maryon Tower, a proto-CN Tower that could have erased the company's College Street store in the early '70s.

Had it been built, the roof of the triangular concrete, steel, and glass tower would have been higher than New York's original World Trade Centre. At its core - literally - would have been a giant radio and TV antenna; tall downtown buildings were deflecting signals, which was one of the reasons the CN Tower became a necessity.

The eponymous Maryon was an expert in tall buildings and he confidently predicted his design would deflect winds of up to 200 km/h and stand for "1,000 years."

Eaton's was forced to back off when things began to go awry down on Queen Street. The company had been unable to build another much-desired office complex (more on that later) and declining sales later in the decade ensured Maryon's mega tower died and stayed dead.

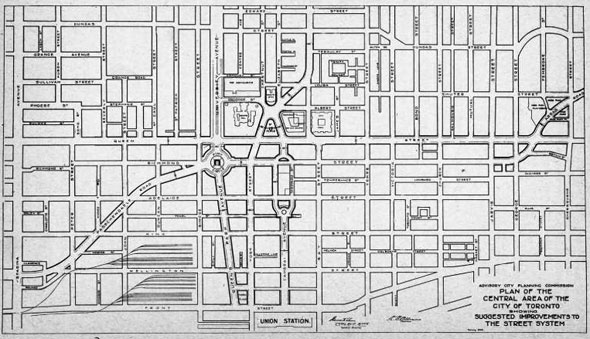

CAMBRAI AVENUE AND VIMY CIRCLE For the most part, Toronto's street grid has remained relatively untouched by mass reconfiguration. Unlike Paris, which had its famous avenues carved out en masse by Baron Haussmann in the 19th century, Toronto has never been significantly made over, though proponents of the various downtown expressway concepts tried.

For the most part, Toronto's street grid has remained relatively untouched by mass reconfiguration. Unlike Paris, which had its famous avenues carved out en masse by Baron Haussmann in the 19th century, Toronto has never been significantly made over, though proponents of the various downtown expressway concepts tried.

Cambrai Avenue, Vimy Circle, Passchendaele Road, the principal features in Toronto's ill-fated make-over plan, would have carved through the area between Front, Spadina, Queen, and Yonge to create a large traffic circle (Vimy) just south of where Osgoode station is now, and two broad streets, one running north from Union Station to Queen (Cambrai), and another winding from Wellington and Spadina to Queen and University (Passchendaele.)

The principal features of the plan, a revised and distilled version of an earlier scheme, all took their name from key battles of the first world war. St. Julien Place, a small public garden, was imagined in the centre of Cambrai Avenue, just south of Queen.

The project was halted (for the most part) by the will of the people in January 1930. A question on the municipal ballot sought authorization to finance the project just months after the stock market crash and, not surprisingly, the "no" voters prevailed by about six per cent.

That said, the now lost Registry of Deeds and Land Titles office and the extension of University Ave. to Front St., both pieces of the plan, were built.

EATON CENTRE TOWERS Before Eaton's conceived of its downtown shopping mall, an entirely different scheme was in the works for Queen and Yonge that involved the destruction of Old City Hall for, you guessed it, office towers.

Before Eaton's conceived of its downtown shopping mall, an entirely different scheme was in the works for Queen and Yonge that involved the destruction of Old City Hall for, you guessed it, office towers.

Eaton's wasn't erasing itself, far from it. A new flagship store and shopping atrium - the largest in the world, no less - was planned for the northwest corner of Queen and Yonge. Behind it, at the expense of the recently defunct Old City Hall, would rise a whopping 69-storey central tower, three office buildings (two 57-storeys, one 32,) and a 20-storey cylindrical hotel, a nod to the new City Hall building just to the west.

The collection of matching towers would be set in a large swath of open space, similar to Mies van der Rohe's TD Centre.

The original Eaton Centre seemed destined to become reality when Eaton's abruptly pulled the plug amid discussions about retaining Old City Hall in May 1967. The company said the proposed stipulations and limitations had made the project unsustainable and its executives refused to meet with officials from Metro Toronto who were keen to reach a deal.

The blueprints went in the garbage for good in 1967. In 1968, the Eaton Centre mall as we know it was proposed.

For more unbuilt delights and greater detail on several of these mega projects, Mark Osbaldeston's Unbuilt Toronto: A History of the City that Might Have Been and Unbuilt Toronto 2: More of the City That Might Have Been, both of which provided details included in this post, are well worth a read.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: City of Toronto Archives, Toronto Telegram Archives, Toronto Public Library.