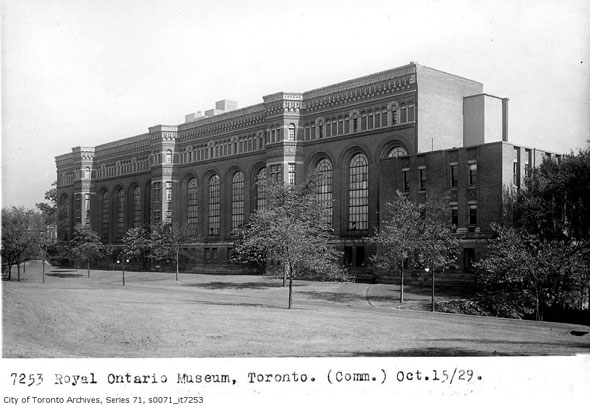

The treasure trove of rare jewels, glittering gems, and ancient fossils that became the Royal Ontario Museum was originally imagined by architectural firm Darling and Pearson as a cavernous Italianate structure capable of dominating the corner of Bloor Street and Queens Park Crescent.

The treasure trove of rare jewels, glittering gems, and ancient fossils that became the Royal Ontario Museum was originally imagined by architectural firm Darling and Pearson as a cavernous Italianate structure capable of dominating the corner of Bloor Street and Queens Park Crescent.

The design had four matching sides galleries arranged in a rough square. A grand entrance flanked by two matching towers was drawn facing Bloor Street and something even more elaborate was planned for the main facade on Queens Park Crescent. It was to be "one of the finest museums on the continent," wrote the Toronto Star.

Unfortunately, budgetary constraints imposed by the province, which was paying for the construction and half the running costs, meant each block would have to be built separately, starting with the west wing facing Philosopher's Walk. The others would be added later when more money was available.

That original wing, which was considerably smaller though no less impressive, and the institution that was established to operate it turned 100 years old yesterday.

Construction of the province's first purpose-built museum didn't entirely go to plan: Two men were killed when a temporary wooden floor over the top of an elevator shaft collapsed, sending a group of workers more than 80 feet into the basement. "I was just saying to the men that we were just about finished without a single accident of any account," said Professor Corelli, the superintendent of the museum.

Construction of the province's first purpose-built museum didn't entirely go to plan: Two men were killed when a temporary wooden floor over the top of an elevator shaft collapsed, sending a group of workers more than 80 feet into the basement. "I was just saying to the men that we were just about finished without a single accident of any account," said Professor Corelli, the superintendent of the museum.

The $400,000 building that showed its best side to Varsity Stadium was opened on Mar. 14, 1914 by the governor general, Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, the seventh child of Queen Victoria, on the eve of the first world war. Inside was thousands of precious items sourced from the various departments at the University of Toronto.

The first displays must have been a wonder to early visitors. The 300-foot hall on the ground floor, divided down the middle by a geological map of Canada, was packed with gleaming jewels, gold from the Canadian Shield, and lumps of silver from the mines of Cobalt, Ont.

The first displays must have been a wonder to early visitors. The 300-foot hall on the ground floor, divided down the middle by a geological map of Canada, was packed with gleaming jewels, gold from the Canadian Shield, and lumps of silver from the mines of Cobalt, Ont.

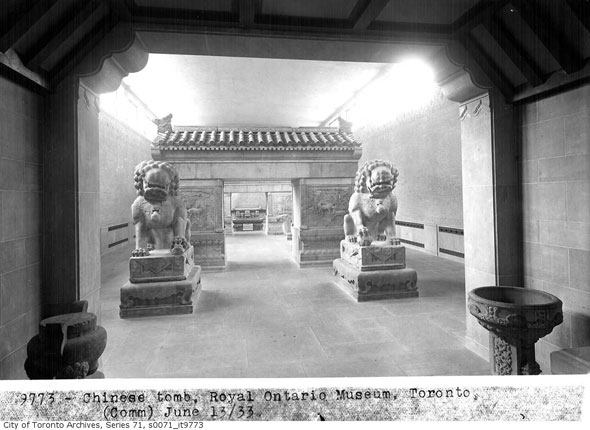

There were Egyptian artifacts, including a "large alter of libations" from about 2700 BC, donated by a Dr. Robert Mond. Roman garments, embroidered curtains, and other treasures sealed inside glass cases or tucked in alcoves along the exterior walls.

The main attraction, however, was the museum of palaeontology on the first floor, in to which staff had squeezed some 60,000 animal specimens from 15,000 species. There was a giant trilobite found near St. John, N.B. - the only one of its kind, the Star said - and several smaller examples from around Toronto, one of which was found at the Don Valley Brick Works.

The main attraction, however, was the museum of palaeontology on the first floor, in to which staff had squeezed some 60,000 animal specimens from 15,000 species. There was a giant trilobite found near St. John, N.B. - the only one of its kind, the Star said - and several smaller examples from around Toronto, one of which was found at the Don Valley Brick Works.

Several dinosaur skeletons were lovingly assembled and presented on marble plinths. A "sea-going reptile" that measured 16-feet in length - possibly a plesiosaur - had pride of place beside an "almost perfect and very valuable" Moa, a massive flightless bird hunted to extension by the New Zealand Maori in the 1400s.

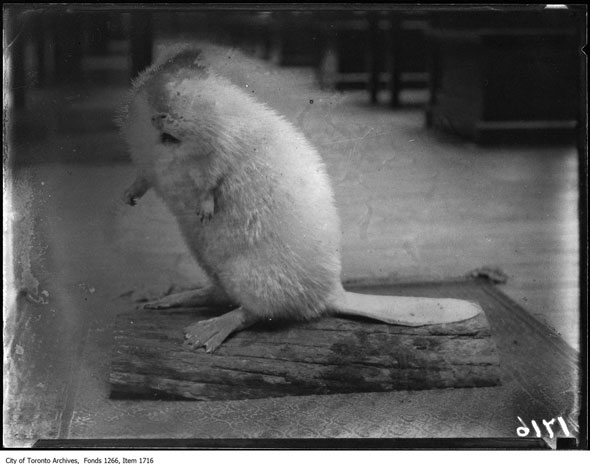

Though the museum tried to steer clear of curios and remain strictly educational, there were several delightfully odd exhibits. An albino beaver of unknown provenance was mounted on a piece of wood (minus its eyes) and a shark's tooth workers claimed had been found in Toronto was given special attention in the newspapers at the time.

Though the museum tried to steer clear of curios and remain strictly educational, there were several delightfully odd exhibits. An albino beaver of unknown provenance was mounted on a piece of wood (minus its eyes) and a shark's tooth workers claimed had been found in Toronto was given special attention in the newspapers at the time.

The tale went that workers digging the 40-foot foundation for the Board of Trade Building at Front and Yonge streets had found the bizarre artifact deep underground during a routine excavation. The Star called it an "unsolved mystery" and left it at that. The ROM was happy to leave a question mark over the find, too, though the tooth does appear to have been verified as genuine.

"If it came by natural agencies its presence here is a mystery yet unsolved," The Star wrote.

(Interestingly, more than a hundred years later, when the TTC was excavating the streetcar tunnel beneath Bay Street, workers turned up a section of orca vertebrae that no-one has since conclusively explained. Early predictions that it was a discarded piece of a whale once displayed in an early zoo at Front and York streets seem to have been disproved, however. Serendipitously, the mystery bone is on display at the ROM today.)

In all there were 10 alcoves in the palaeontology section: protozoa and sponges; corals; crinoids; crystals, blastoids, asteroids and echinoids; bryozoa; brachiopods; pelecypods; cephalopods; gastropods; arthropods.

In all there were 10 alcoves in the palaeontology section: protozoa and sponges; corals; crinoids; crystals, blastoids, asteroids and echinoids; bryozoa; brachiopods; pelecypods; cephalopods; gastropods; arthropods.

"The names sound most forbidding, but the specimens themselves are fascinating for the layman and the student alike," a preview of the museum's offerings calmly assured its readers.

The Royal Ontario Museum was finally expanded to its intended size with the addition of the east wing in 1933. The space to the south of the H-shaped structure was filled by a curatorial building and the Bloor Street face was home to the Queen Elizabeth II Terrace Galleries until the arrival of Daniel Libeskind's loved-and-loathed crystal addition in 2007.

A year-long program of events is planned to celebrate the ROM's centenary.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: City of Toronto Archives, Royal Ontario Museum