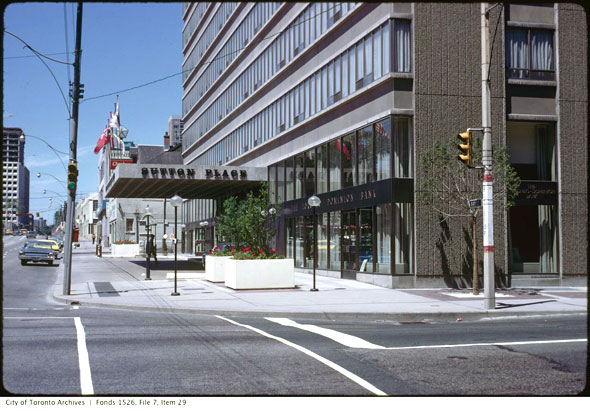

The Sutton Place Hotel, the former luxury residence at Bay and Wellesley that's currently auctioning off its TVs, couches, fireplace mantles, brass wall sconces, anything that isn't bolted down (and some stuff that is,) was, in the 1960s, undoubtedly the most prestigious place to spend the night in the city.

The Sutton Place Hotel, the former luxury residence at Bay and Wellesley that's currently auctioning off its TVs, couches, fireplace mantles, brass wall sconces, anything that isn't bolted down (and some stuff that is,) was, in the 1960s, undoubtedly the most prestigious place to spend the night in the city.

Liberace and Sofia Loren stayed there, and in later years so did Michael Jackson, Robin Williams, and other stars of stage and screen lured by massive suites furnished in gleaming crystal and polished Italian marble. Even the soap wrappers were custom made.

In a few years the building, once a focal point of the Toronto International Film Festival during its years in Yorkville, will be completely stripped back and reshaped into the Britt Condos.

The 32-storey hotel tower was built in the mid-1960s on the site of the gorgeous and thoroughly intimidating Wellesley Public School, a gothic revival masterpiece that stood on an old creek bed. Builders had to lower the water table beneath the site by some 6 metres and install permanent pumps in the basement to keep out water prior to construction.

The 32-storey hotel tower was built in the mid-1960s on the site of the gorgeous and thoroughly intimidating Wellesley Public School, a gothic revival masterpiece that stood on an old creek bed. Builders had to lower the water table beneath the site by some 6 metres and install permanent pumps in the basement to keep out water prior to construction.

Thanks to a promotional supplement published in The Globe and Mail, we have detailed information about the physical structure of the building. The concrete and steel supporting structure weighed 36,000 tonnes and was 113 metres from its deepest excavation point to the top of the roof. At it's narrowest point, the building was just 20 metres wide.

The project represented a $12 million investment for its owners, who had earlier considered building apartments on the site. But the building was never about outward beauty.

When the Toronto Sutton Place Hotel opened in the summer of 1967, one in a chain named for an affluent Manhattan neighbourhood, there were 225 guest rooms and dozens more luxury apartments on the upper floors: A combination of "old-world charm and space-age elegance," the advertisers said. "The new showplace of Toronto."

"Sutton Place has Spanish bedspreads and English coach lights and two year-round swimming pools and every item in the hotel was custom ordered," the hotel boasted. "This includes 100 dozen dinner plates and 50 dozen tablecloths and 400 gold nylon shower curtains and 8,100 square yards of broadloom [carpet] and 120 escargot clamps for eating snails."

In the lobby, a 6,000 prism chandelier hung near a 23-metre historical mural that depicted the first 100 years of Canada's history. The plexiglass, gold, silver, and copper piece by Philadelphia artist Shirley Tattersfield was, for reasons that aren't entirely clear, designed to be practically indestructible. It could withstand 990 Celsius temperatures and blows from a sledgehammer, she said. "It'll last longer than anything in the hotel."

There was a pub-style lounge, a dining room, a coffee house, a banquet hall, and 650 square metres of office space that overlooked a sun patio. Up on the roof, the highest neon sign in Toronto (Sutton Place was the 4th tallest building in the city in 1967) spelled out the name of the hotel in massive 2.5 metre letters.

People with enough money to stay at Sutton Place were pampered by a team of impeccably uniformed staff, several of whom had European training, a fact the hotel was eager to point out. Ellen Harris, the manager of the hotel cafe, literally wrote the book on customer care - Professional Restaurant Service - and all waitresses were sent away on an intensive seven-day training course in proper serving techniques.

People with enough money to stay at Sutton Place were pampered by a team of impeccably uniformed staff, several of whom had European training, a fact the hotel was eager to point out. Ellen Harris, the manager of the hotel cafe, literally wrote the book on customer care - Professional Restaurant Service - and all waitresses were sent away on an intensive seven-day training course in proper serving techniques.

Continuing the tradition of importing just about every fixture, apparently just for the sake of calling it "imported," the bedrooms were decked out in a dizzying mix of materials: Mediterranean bedspreads, bamboo drapes from San Francisco, ceiling lights from Hamburg, and Swedish table lamps. "All told, more than 56 countries contributed products or materials," hotel management said.

On the ground floor, the massive stainless steel main kitchen, commanded by head chef Stanley Wieczorek, offered 1960s delights like "pheasant under glass" - pheasant breast in a rich mushroom, wine, cognac, and cream sauce shielded under a cover until it's ready to be eaten. The Sutton Place version was served with a special pheasant-shaped plush that looked a like a tea cosy.

The crowning feature of the Sutton Place tower was Stop 33, the top-floor cocktail lounge, restaurant and observation deck topped with a "midnight sky" ceiling of some 2,700 tiny individual light bulbs.

56 floor-to-ceiling windows provided panoramic views of the city at a time when there were few other tall buildings to obstruct the vista. The obsidian towers of Mies van der Rohe's TD Centre, the curving clasp of City Hall, and the Canadian Bank of Commerce building were the only obstructions to the lake.

But it wasn't all monogrammed towels and room service. The opulent surroundings were rocked just three months after opening day when a bomb hidden inside the box spring bed of stock promoter Myer Rush exploded, blasting glass, bedding, and shrapnel from a sixth floor window into the street, shortly before 4 AM on Nov. 10 1967.

But it wasn't all monogrammed towels and room service. The opulent surroundings were rocked just three months after opening day when a bomb hidden inside the box spring bed of stock promoter Myer Rush exploded, blasting glass, bedding, and shrapnel from a sixth floor window into the street, shortly before 4 AM on Nov. 10 1967.

Rush, who was due in court the next morning to face charges in an alleged $100 million stock fraud, was critically injured: "His head, chest, and side were caved in by the force of the explosion," wrote the Toronto Star. "He was moaning 'help me, please help me,'" Fire Captain John Bird said. Paramedics thought he had a 10 per cent chance of survival.

The bomb had been hidden under the mattress in room 615 and wired to a dime-store alarm clock. Rush - who was "built like a box" and spoke as if he had "gargled with ground glass" - had probably been sleeping on top of it for close to four hours. The force of the explosion left him crumpled against the door of the room; firefighters had to break it down because the night latch was still on.

The stock promoter who had long been under police suspicion was a popular target: Earlier in the year he had been asked to select from a police line up the man who had worked him over with a baseball bat and stolen $9,000 of his money. He made his choice by punching the culprit in the face.

Amazingly, Rush survived the attempt on his life and continued his life of nefarious dealings, fleeing overseas before eventually returning to Canada in 1969 to face a 10-year jail sentence.

The Sutton Place Hotel was open for 45 years. It closed for the last time in June 2012.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Image: Sutton Place Hotel, City of Toronto Archives, Toronto Public Library