When the TTC signed an agreement with Metrolinx to bring full-scale Presto facilities to the subway, streetcar, and bus network this week it officially set a funeral date for its humble token. In 2015, when riders will pay fares by electronic card or cash, the token will have no place in the fare box.

When the TTC signed an agreement with Metrolinx to bring full-scale Presto facilities to the subway, streetcar, and bus network this week it officially set a funeral date for its humble token. In 2015, when riders will pay fares by electronic card or cash, the token will have no place in the fare box.

The little coins date back to the 1950s when counterfeiters were becoming increasingly adept at forging paper tickets and the TTC was keen to update its fare payment system for the opening of the Yonge subway. It would be a while before crafty crooks would find a way to skip out on fares, but they got there in the end.

Getting the first batch of 10 million tokens made wasn't without controversy. Local stamping businesses cried foul when the TTC awarded the contract to Southam Press Co., a Montreal firm, without properly circulating the specifications locally. Two owners quoted in the Toronto Star said they had bid assuming the coins would be approximately the size and weight of a nickel. Southam Press won because their lowest bid correctly established the roughly dime-sized proportions.

Getting the first batch of 10 million tokens made wasn't without controversy. Local stamping businesses cried foul when the TTC awarded the contract to Southam Press Co., a Montreal firm, without properly circulating the specifications locally. Two owners quoted in the Toronto Star said they had bid assuming the coins would be approximately the size and weight of a nickel. Southam Press won because their lowest bid correctly established the roughly dime-sized proportions.

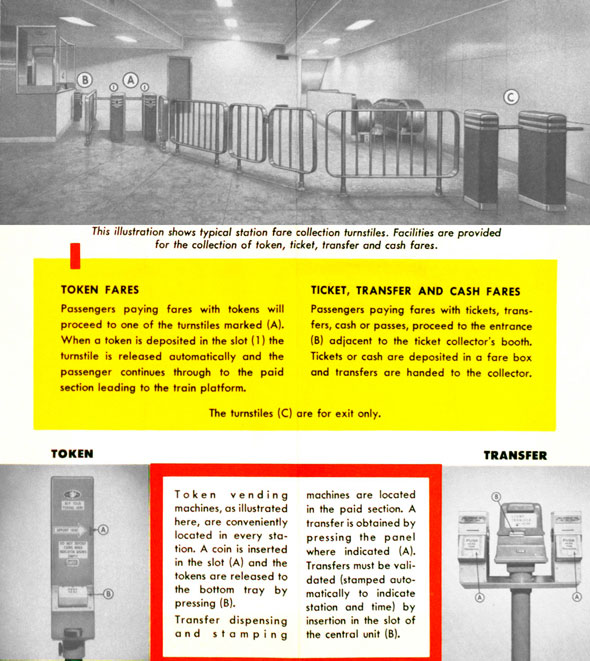

The first fares paid with a dedicated coin were pushed into brand new automatic turnstiles under Yonge street when Canada's first subway opened in 1954. An instructional leaflet circulated at the time told passengers how to purchase a token from an automatic machine (one for 15 cents, four for 60) and proceed into the underground. For nostalgia buffs, two of these original-style turnstiles are still in place at Sherbourne station.

The first generation tokens were made of aluminum with a simple "good for one fare" message stamped on the verso. In case anyone got confused by the concept, special guides were on hand to answer questions and explain the idea of a valueless coin to commuters.

The TTC introduced a fare zone system - an idea it would tweak over the years - in 1954 that offered five tokens for 50 cents instead of three for a quarter. It was only the second fare hike in the Commission's history and was naturally met with some resistance. The "single-fare zone" encompassed Forest Hill, Leaside, East York, Swansea, and the core of the city; travel to the townships outside required a second coin. Despite the concerns, the Star promised "Toronto will likely still hold the lead for efficient and inexpensive transportation."

The TTC introduced a fare zone system - an idea it would tweak over the years - in 1954 that offered five tokens for 50 cents instead of three for a quarter. It was only the second fare hike in the Commission's history and was naturally met with some resistance. The "single-fare zone" encompassed Forest Hill, Leaside, East York, Swansea, and the core of the city; travel to the townships outside required a second coin. Despite the concerns, the Star promised "Toronto will likely still hold the lead for efficient and inexpensive transportation."

The automatic vending machines, which were beset with technical problems from day one, couldn't be recalibrated to dispense more tokens under the new system and the TTC seriously considered ditching the three-month old tokens altogether. The machines were so bad that maintenance crews worked nights just to keep them running.

The automatic dispensers were removed for several months to iron out these kinks while an experimental single token dispenser was tested at King station in 1960.

During this time it was possible to buy tokens in any amount from the ticket booth at subway stations and from guides. For reasons that aren't entirely clear, disgruntled TTC workers occasionally refused to do sell single tokens, prompting reprimands and a note in the newspaper.

As the value of a token increased with each fare hike, the TTC had to adapt the way it operated to prevent people buying in bulk and hoarding the coins for months, something that continues to be a problem. As their popularity grew, customers complained the dime-sized pieces were too easy to mix up with regular change and so square and even triangular replacements were considered.

As the value of a token increased with each fare hike, the TTC had to adapt the way it operated to prevent people buying in bulk and hoarding the coins for months, something that continues to be a problem. As their popularity grew, customers complained the dime-sized pieces were too easy to mix up with regular change and so square and even triangular replacements were considered.

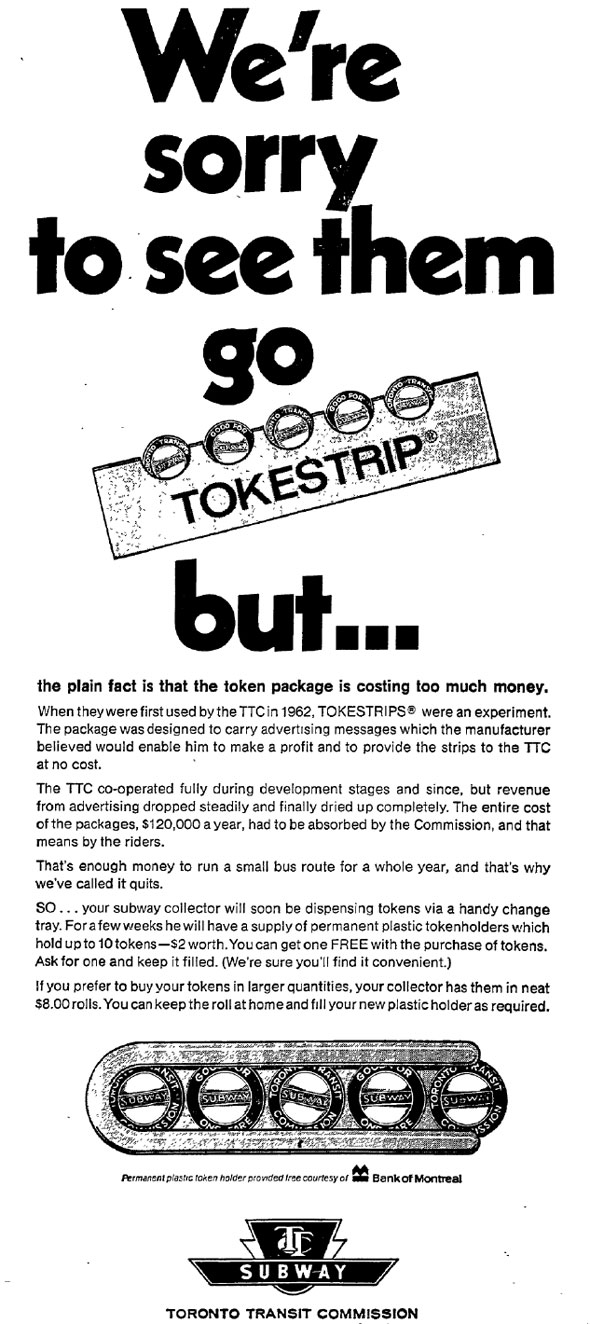

Instead, the solution came in the form of a red paper container with the druggy name "Tokestrip" which was capable of holding seven tokens and cost a $1 with all purchases of multiple tokens. This was later replaced with a plastic version sponsored by the Bank of Montreal, much to the annoyance of Peter H. Storm, the lone man making them. "The public simply won't be bothered with these new containers," he confidently declared, assuming the public would rage for his tear-off container's return. They didn't.

A new, significantly heavier brass token with a large version of the TTC crest on the face and a "winged symbol" (what would eventually become the current logo) on the back replaced the original coinage in 1963. Five years later a special commemorative edition was minted to celebrate the opening of the Bloor-Danforth extension to Islington and Warden stations.

A new, significantly heavier brass token with a large version of the TTC crest on the face and a "winged symbol" (what would eventually become the current logo) on the back replaced the original coinage in 1963. Five years later a special commemorative edition was minted to celebrate the opening of the Bloor-Danforth extension to Islington and Warden stations.

The coins made in the 1960s would remain the TTC's token of choice until 2006 when the FBI busted a giant counterfeiting ring specializing in slugs capable of fooling Toronto's automated turnstiles and all but the most diligent of operators. The illegal operation made roughly 5 million fake tokens from its base in the United States, costing the cash-strapped TTC roughly $10 million in lost revenue.

The fakes were sold at steep discounts through a loose network in bars, outside stations, workplaces, and online. The only sure way to spot a fake was tighter than normal spacing on the embossed lettering. In the fallout from the scam, the TTC promised an entirely new transit currency would be in place within a year.

The replacement tokens, stamped by Osborne Coinage, an American company, would be the final metal fares to circulate in Toronto and were designed to be harder to forge - the swirled pattern on the edges makes it harder for bootleggers to cut a fake stamp plate.

When the first batch of 20 million high-security coins were released in late 2006 at a cost of $1.7 million (8.5 cents each) the TTC attempted to coin the nickname the "teeny-tiny toonie." It didn't. Nevertheless, the tokens will no doubt be missed when they are finally dropped for good in the next three years.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: City of Toronto Archives, public domain, and "TTC Tokens from 1954 & 2012" by Brian.Nguyen in the blogTO Flickr pool.